Robert E. Lee and the “New South”

An honest retrospective of Lee’s role in redefining the post-war South.

The “New South” was a term coined in 1874 by Henry Grady, journalist and editor of The Atlanta Constitution. Grady contrasted the antebellum economy and society, which was based on slave labor, a plantation economy reliant on a few cash crops such as cotton, tobacco, and rice, a poor railway system, and little industrialization with his vision for the post-war South. Grady rejected the economy and traditions of the Old South and the slave-based plantation system.

Supporters of a “New South” demanded a modernization of attitudes and society in order to reintegrate the South into the nation as a whole. They called for racial and sectional reconciliation and for Northern investment in the South.

Grady and others wanted a diversified agricultural program, industrialization, and a modern railway system to connect parts of the South to each other and to the North. Henry Grady promoted public education for both white and black Americans, but in separate schools. This led to the concept of “separate but equal” schools that was eventually ruled unconstitutional in 1954. Grady was particularly interested in technical education and successfully lobbied for the creation of the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) in 1887.

Robert E. Lee was a precursor of the “New South” movement from his surrender at Appomattox until his death in October 1870. In 1886, Grady acknowledged his debt to Lee: “When Lee surrendered … the South became and has since been loyal to the Union.” (1)

Immediately after Appomattox, Lee gave an interview to The New York Herald in which he stated that “he was ready to make any sacrifice or perform any honorable act which would lead to the restoration of the country.” (2)

He maintained this posture throughout his life and was considered the major figure in the South promoting reconciliation and harmony between North and South. Responding to a widow who expressed animosity toward the North, Lee said, “Madame, don’t bring up your sons to detest the United States government. Recollect that we form one country now. Abandon all these local animosities and make your sons Americans.” (3)

Lee opposed slavery before the Civil War and called it a “moral and political evil.” After the war, he proclaimed that “So far from engaging in a war to perpetuate slavery, I have rejoiced that slavery is abolished. I believe it will be great for the interests of the South.” (4)

For the five and one half years from Appomattox until his death, Lee focused on rebuilding Virginia and the South academically, economically, and morally. According to one noted historian, “This was his visionary moment.” (5)

The primary focus of his efforts was in education. He became the President of Washington College, where he established a modern curriculum based on such subjects as modern languages, business, journalism, engineering, and law. He saw a practical as well as purely intellectual use for education.

Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) became a model for other institutes of higher education in the South, and its graduates and professors became leaders of Southern revitalization. According to the authors of one study, “Washington College under Lee’s leadership was progressive, embodying a vision of a New South.” (6)

Lee favored the education of black as well as white people. In testimony before Congress in 1866, Lee was asked how he felt about the education of black people. He said, “Where I am … the people have exhibited a willingness that the blacks should be educated, and they express an opinion that that would be better for the blacks and better for the whites.” (7) Lee felt that the most important thing was to educate African Americans in specific skills and for civic responsibility.

Lee sought the support of Northerners in his progressive education efforts. Henry Ward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, lauded Lee as “the very man to take charge of a great educational institution in the South” and urged generous financial assistance for Washington College on “behalf of the common education of the whole people, for the sake of reconstruction, reunion, peace, and love.” (8)

Lee quickly became a fundraising juggernaut, doubling the endowment of Washington College within two years. He attracted significant benefactors from the North: George Peabody, an international financier, Peter Cooper, an industrialist and inventor; Thomas Scott, the owner of the Pennsylvania Railroad; W.W. Corcoran, a banker; Warren Newcomb, a sugar merchant; and Horace Greeley, a newspaper editor, publisher, and future presidential candidate. Cyrus McCormick, a native of Rockbridge County and inventor of the mechanical reaper, was also a significant donor.

Robert E. Lee was also a supporter of a diversified agricultural system and internal improvements. He introduced classes on modern agricultural methods and business at Washington College. Lee served as the second President of the Valley Railroad from 1869 until 1870 but died before work had begun on the line.

One of those who followed Lee’s lead in education was William Henry Ruffner. Ruffner’s father, Henry Ruffner, had been President of Washington College from 1836 until 1848. He was a progressive educator who advanced the cause of public education. W. H. Ruffner was living in Lexington during Lee’s presidency, and they shared a vision of education, which included all classes of people and both public and private schools. When Ruffner became a candidate for Virginia’s first Superintendent of Public Schools in 1870, Lee wrote a letter of recommendation for him stressing their common views.

Ruffner was referred to as the “Horace Mann of the South” after the pioneering Massachusetts public school advocate. Virginia established the first free, public school system in the South after the Civil War, and Ruffner developed a comprehensive plan for elementary through high school education and beyond. His plans for Virginia were based on Northern models as there were very few public schools in the South at the time. During his time as Superintendent (1870-1882), he called for and established teacher institutes and normal schools. Ruffner also believed in technical and practical education and was a founding member of Virginia Polytechnic Institute (Virginia Tech).

Ruffner also supported the education of black people. In 1873, when running for reelection as superintendent, he pledged to extend “the blessings of education with absolute impartiality to all classes, rich and poor, black and white.” (9) Ruffner denied that black people were intellectually incapable: “It is utterly denied that there is any such differences between the two races insusceptibility of improvement as to justify us in making the Negro an exception to the general conclusion of mankind in respect to the value of universal education.” (10)

He was sometimes opposed by conservative politicians because of his support for black education and his “radical” views of education in general. The election of James Kemper as Governor in 1873 provided Ruffner with a like-minded ally. Kemper was a classmate of Ruffner at Washington College prior to the war and significantly increased the number of black and white public schools during his administration.

Ruffner served on the original board of trustees of Hampton Institute, Virginia’s black land grant institution. In 1873, he addressed the students and a number of northern visitors “and held out to them [i.e. the students] the promise of their great future as citizens of Virginia.” (11)

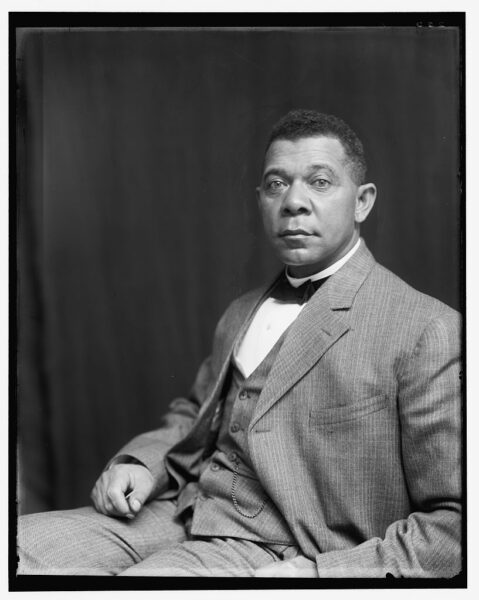

Among the audience that day was a young Booker T. Washington, who would go on to establish the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Washington had a long history with the Ruffner family and had lived with Lewis and Viola Ruffner in West Virginia after the Civil War. Viola Ruffner provided some rudimentary education for Booker and helped him to attend Hampton. She remained his lifetime friend. Viola Ruffner was William Henry’s aunt, and he knew Booker’s story. Ruffner was an admirer of Booker T. Washington and his approach to education and black progress.

William Henry Ruffner was something of a Renaissance man. He was a Presbyterian minister, an educator, an author, and a geologist. Following his tenure as superintendent, he became the founding President of the Longwood State Female Normal School (now Longwood University) and supported female education throughout his life.

In 1882 he made his first trip to Birmingham, Alabama to inspect the mining industry there. As a result of his explorations and surveys, new iron ore deposits were discovered which helped to make Birmingham a manufacturing and mining center and a focus of the “New South” movement.

Despite his support for black education, Ruffner opposed integrated schools as impractical and politically unfeasible at the time. In this his position was not different from the public stance taken by Booker T. Washington.

Washington has been criticized for his “accommodationist” views in recent years, but he was a practical man who knew what could and could not be accomplished in the South of his era. At the time, he was considered the primary leader of the African American community in the South and throughout the nation. He was much admired by New South leaders like Henry Grady, and, like Lee at Washington College, he attracted the support of many Northern benefactors for the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

Washington, in turn, admired Robert E. Lee because of Lee’s concerns for the plight of African Americans before the war and his desire to bring about reconciliation after the war. In 1909, Washington wrote, “I am tempted to say that it certainly requires as a high degree of courage for men of the type of Robert E. Lee … to accept the results of the war in the manner and spirit in which they did, as that which Grant and Sherman displayed in fighting the physical battles that saved the Union.” (12) In 1910, he said that “The first white men in American, certainly in the South, to exhibit their interest in the reaching of the negro . . . were Robert E. Lee and ‘Stonewall’ Jackson.” (13)

Like Lee and Ruffner, Washington stressed basic education and vocational training for black people. He believed in the philosophy of “self-help” and in the establishment of black businesses. In return for the support of Northern and Southern whites, he remained silent on political issues such as integration and the vote. Still, Washington was responsible for providing practical education to generations of black people and for promoting the cause of African Americans throughout the South and the nation.

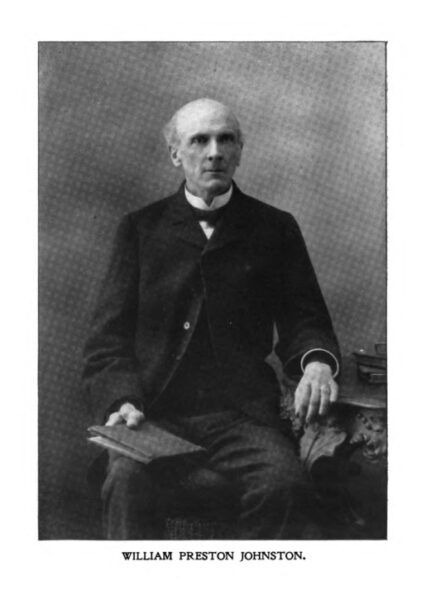

Another acolyte of Lee was William Preston Johnston. William Johnston was the son of Albert Sydney Johnston, the famous Civil War commander. In 1867, Lee invited him to become Chair of History and English Literature at Washington College. He remained in that position until 1877.

Johnston was intimately involved in Lee’s efforts to modernize the educational program at Washington College. Like Lee, Johnston supported other progressive causes such as railroad development. Like Ruffner, he was in favor of public education, teacher’s institutes, and female education.

In 1880, he was selected as the President of Louisiana State University and began to reorganize the institution along progressive lines. In 1884, Johnston became the first President of Tulane University.

His plan for Tulane was similar to that of Lee for Washington College. There Johnston established a college of arts and sciences as well as technology, law, and medicine departments, and Sophie Newcomb Women’s College.

In 1900, Reverend A. D. Mayo wrote Johnston’s obituary and compared him to S. C. Armstrong, the first President of Hampton Institute. Mayo said that Armstrong and Booker T. Washington did for black education what Johnston did for white education. Further, Tulane had the broadest educational program in the South and could be compared favorably to the “new” University of Chicago. (13) In effect, Tulane fulfilled Lee’s vision for a comprehensive, Southern university.

While at W&L, Johnston had contact with some of the Northern philanthropists who had provided funds to the school. At Tulane, he was able to gain the financial support of the Peabody Educational Fund and, most importantly, of Warren Newcomb’s widow, who basically endowed Sophie Newcomb College.

Johnston also adapted Lee’s concepts of student self-governance and an honor system to Tulane. In an 1893 address, Johnston called for a complete educational system in Louisiana — including primary, secondary, collegiate, and university education. He called for public high schools in every parish of the state and for technical and professional training. (14) Johnston was also instrumental in the establishment of the public library system in New Orleans.

Many other individuals associated with Washington and Lee — professors, former professors, and alumni — promoted and implemented parts of the New South vision in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These included railroad and industrial development, the popularization of science and technology, modern agricultural techniques, and not just female education but education.

As late as 1936, The Chattanooga Times said that “Robert E. Lee, as a college president, was the real architect of the New South.” (15) The irony is that while supporters of The Lost Cause looked to an idealized past exemplified by a mythological Lee, Lee himself and those whom he inspired after 1865 looked to the future with a clear vision and specific plans for implementing that vision.

References:

1. Henry Grady, ” Address to the New England Club in New York, 1886″, reprinted in Paul D. Escott and David R. Goldfield, Major Problems in the History of the American South, v. II, The New South (Lexington, Mass.: D.C. Heath and Company, 1990), 71-73.

2. Thomas M. Cook, ” Interview with General Lee,” New York Herald, April 29, 1865.

3. Lee quoted in Edward Lee Childe, The Life and Campaigns of General Lee (London: Chatto and Windus, 1875), 331.

4. John Leyburn, ” An interview with General Robert E. Lee, ” Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, V. XXX, New Series, V. VIII ( May to October, 1885), 167.

5. Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters (New York: Viking Press, 2007), 473.

6. L Neal Holly and Jeremy P. Martin, ” Leadership in Crisis: A Historical Analysis of two College Presidencies in Reconstruction Virginia, ” Higher Education in Review, v. 9 (2012), 60-61.

7. ” Robert E. Lee’s Testimony before Congress, February 17, 1866,” 39th Congress, 1st Session, House Report no. 30, pt. II, 129-30.

8. Beecher quoted in “Education at the South,” New York Observer and Chronicle, 46:10 ( March 5, 1868), 78; and in Brooklyn Union, March 3, 1868, 2.

9. Walter J. Fraser, Jr., ” William Henry Ruffner and the Establishment of Virginia’s Public Schools, 1870-1874,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 79, no. 3 (July, 1971), 276

10. Ibid., 268.

11. Ibid., 271.

12. Booker T. Washington, ” An Address on Abraham Lincoln, delivered before the Republican Club of New York City,” February 12, 1909, published in Tuskegee, Alabama, 1909, 9-10.

13. Rev. A.D. Mayo,” William Preston Johnston’s Work for a New South,” Chapter XXX from The Report of the Commissioner of Education, 1898-99 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1900), 367-371.

14. William Preston Johnston, ” The Demand for High Schools in Louisiana,” An Address to the Convention of Parish Superintendents at Lake Charles, Louisiana, Wednesday, June 28, 1893 (New Orleans: L. Graham and Sons, 1893).

15. In Jennifer D. Page, ” The Forgotten Sins of Robert E. Lee: How a Confederate Icon Became an American Icon” (Senior Thesis, Salve Regina University, 2019), 13.

Opinion Robert E. Lee New South

M. Neely Young, Ph.D., ’66