W&L in the “Bigs”: Washington and Lee Alums who played Major League Baseball

Student Tubby Stone created the Trident in 1904

Written by Neely Young

Washington and Lee University is one of the oldest college and universities in the United States and is known for its outstanding liberal arts education. It has produced numerous, illustrious graduates primarily in the professions- business, law, education, medicine, etc. Some of its most famous graduates include:

- John J. Crittenden, U.S. Senator from Kentucky who fashioned the Crittenden Compromise to try to avoid the Civil War.

- John W. Davis, ambassador to Great Britain and Democratic nominee for the presidency in 1924.

- Senator Bill Brock, TN.

- Senator John Warner, VA.

- Mark Short, Chief of Staff to Vice-President, Mike Pence.

- Supreme Court Justice, Lewis F. Powell.

- Federal Judge Mike Luttig, who advised Mike Pence during the constitutional crisis surrounding the 2020 Presidential election.

- Sydney Lewis, founder of Best Products Company

- Christopher Chenery, businessman and owner of the Triple Crown winner, Secretariat

- Archibald Alexander, President of Hampden-Sydney College and founder of Princeton Theological Seminary

- “Pat” Robertson, T.V. evangelist and founder of Regents University

- John Chavis, Presbyterian minister and first African American to graduate from a college or university in the U.S.A.

- Roger Mudd, journalist.

- Authors Thomas Nelson Page, Tom Robbins, and Tom Wolfe

- Cy Twombly, artist

- G. Davis Low, astronaut

- Meriweather Lewis, American explorer ( this claim is in dispute)

What W&L is not known for is the production of professional athletes. This is largely because the university dropped subsidized athletics in the early 1950’s and has competed on a purely amateur basis ever since. However, there was a time from the late 19th century until the early 1950’s when several professional baseball and football players came out of the school. This period coincided with a time when Washington and Lee was competing in “big time” college athletics. As the National Basketball Association (N.B.A.) was not formed until 1946 and was in its infancy when W&L eliminated subsidized athletics, no university graduate has ever played in the N.B.A.

The “National Pastime” of baseball dates back in America to at least the early 1800’s. On June 19, 1846, the New York Nine played the Knickerbockers in the first officially recognized game. Alexander Cartwright had developed the so-called “Knickerbocker Rules” the previous year, and these were to guide the sport henceforth. The first nine-man college game was played in New York city between the Fordham Rose Hill Baseball Club of St. John’s College (now Fordham University) and the College of St. Francis Xavier (now Xavier High School) on November 3, 1859. This game was also played under the Knickerbocker Rules. It is unclear when the first collegiate baseball game was played in the South, but it was likely a game between the “Arlington Club” of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) and the “Monticello Club” of the University of Virginia on May 22, 1868. (1) Washington and Lee also likely participated in the second intercollegiate baseball contest, a “match-game” between Washington College and Virginia Military Institute (V.M.I.) in spring, 1869. In this game, nine men played the same positions played by players today in a nine-inning contest. Although Washington College won this game by the rather lop-sided score of 36-13, there would be many more games between these neighboring schools over the remainder of the 19th century.(2) Washington and Lee, as the school was renamed in 1870, also continued to play U.VA on a fairly regular schedule. In the 1890’s intercollegiate sports at W&L became better organized, and the university began to play other colleges and universities in baseball. The 1892 team was declared the “Champions of the South”, having successfully beaten Fishburne Military, V.M.I., U.VA, University of North Carolina, Vanderbilt, Lehigh, and possibly others. (3)

In the meantime, professional baseball teams had been established. The first all-professional team was the Cincinnati Red Stockings (later the “Red Legs” and then just the “Reds”) which was founded in 1869. In 1876, the National League was founded and consisted of eight teams- Boston Red Caps ( later the Red Sox), Chicago White Stockings (later the White Sox), Cincinnati Reds, Philadelphia Athletics (later the Oakland Athletics), St. Louis Browns, Hartford Dark Blues, Louisville Grays, and Brooklyn Mutuals. Some of these teams are still in existence. In 1892, the National League consisted of twelve teams- Boston Bean Eaters, Cleveland Spiders, Brooklyn Grooms, Philadelphia Phillies, Cincinnati Reds, Pittsburgh Pirates, Chicago Colts, New York Giants, Louisville Colonels, Washington Senators, St. Louis Browns, and Baltimore Orioles. Again, we recognize some of these teams today, while others have changed their name or are in a different league. It was not until 1901 that the American League was established, but by that time there were a number of major league teams and other minor league teams which supplied players for the big leagues. College teams also supplied teams to the majors, either directly or through the minor leagues. Washington and Lee was one of these, and had twelve alums play in the major leagues in the period from 1877-1941.

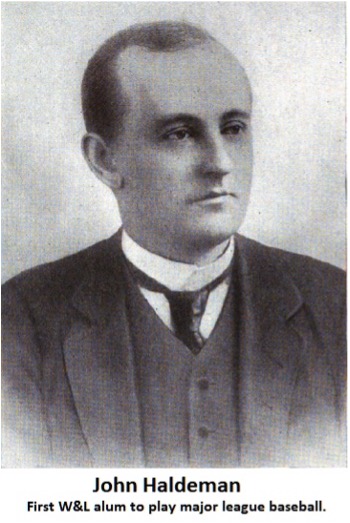

John Haldeman, class of 1876, was the first W&L alum to play in the major leagues. Haldeman’s entrance into the big leagues was accidental and almost comical. He had been a good, but not great, player at Washington and Lee and played for an amateur team upon returning to his hometown of Louisville, KY. His father was the owner of the Louisville Times (later the Louisville Courier-Journal) and President of the Louisville Grays National League baseball team. In 1877, John Haldeman became a reporter and the business manager of the Times. On July 3, 1877, he played his one and only game in the major leagues. One of the infielders for the Grays was injured, and the manager asked Haldeman, who was covering the game for the newspaper, to fill in. This is the only time in major league history that a reporter covering a game played in a game that he was reporting on. After the game, Haldeman returned to reporting on the Grays, who were having a great year. Suddenly in August, they went on a seven-game losing streak with their star pitcher underperforming. Haldeman openly questioned whether the team had deliberately thrown games and the pennant race. Due to Haldeman’s tenacious reporting, four players were eventually found to have thrown games for payment from gamblers. All four were barred from baseball for life. This was the greatest scandal in major league baseball until the infamous Chicago “Black Sox” scandal of 1919. (4)

Dan McFarlan was the second W&L alum to play in the majors. Born in 1873, he played in the minors in 1892 at the age of 18. He did not graduate from W&L but appears to have attended from 1892 to 1894. Dan played again in the minors from 1894-95, making his major league debut with the Louisville Colonels in 1895. From 1896-1898, he was again in the minors, returning to the National League in 1899 with the Brooklyn Superbas and, later, the Washington Senators. He was typical of many ballplayers and many Washington and Lee alum in only having had “a cup of coffee” in the majors. After 1899, he continued playing in the minor leagues until 1907. McFarlan was the first player born in Texas to play in the major leagues. (5)

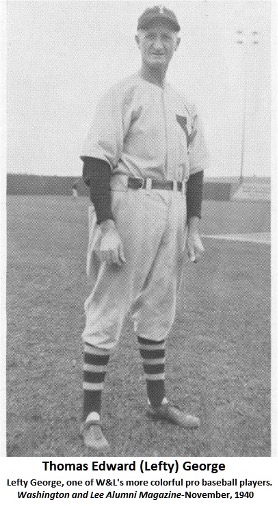

Of the twelve major leaguers produced by W&L, eight of them played in the period from 1908-1924. This was known as the “Golden Era” of Washington and Lee sports with many All-State, All-Region, and All-American athletes in baseball, football, and basketball during this time. One of the most interesting and entertaining of these was Thomas Edward “Lefty” George. George pitched professionally for at least 32 years, from 1904 until early 1944, when he was 57 years old! He pitched on and off in the major leagues from 1911 to 1918, but, like many others, spent much of his career in the minors. Born in 1886, he began pitching semipro ball before graduating from high school, and then played pro baseball for an all-star team called the Pittsburgh Collegians in 1904 while completing his high school career at Pittsburgh’s East Liberty Academy. (6) Following high school graduation in 1905, he attended Staunton Military Academy and pitched brilliantly in the spring of 1906. With restrictions on amateur players being lax at the time, Lefty played pro baseball from 1906 through 1908 for various minor league teams in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. He apparently played under assumed names, including George Miller, in order to protect his amateur statue while earning money for his private school and college tuition. (7)

George enrolled at Washington and Lee in the spring of 1908 intending to pursue a law degree even though he had not begun his undergraduate education. A rumor began to circulate on campus that George was being compensated for his work on the diamond. A group of students encouraged him to sign a document stating that he was enrolled at the university, had not received any compensation from W&L, and did not intend to accept any compensation from the university in future. In other words, he was not a “paid player” as was the case at some other schools at the time. The fact that George had already been playing professional baseball for at least two years prior to his enrollment did not seem to bother anyone. (8) George went on to have a good season with the Generals, finishing with a 3-3-1 record on a team which went 7-8-1. (9). It was during his time as a pitcher at Washington and Lee that he acquired the nickname of “Lefty.” (10)

In the summer of 1908, Lefty returned to Pennsylvania and pitched for the Collegians as well as in the semiprofessional Tri-Borough League. Yet, remarkably, in the spring of 1909 we find him back in Virginia pitching again for Staunton Military Academy at the age of 22. Finally, by the summer of 1909 he abandoned his academic career and begun to play pro baseball full time. He ended the 1909 season with the York White Roses of the Class B Tri-State League composed of teams from Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. He returned to York in 1910 and would end up spending the better part of his life there and marrying a York girl. Toward the end of that season, he signed a deal with the Indianapolis Indians of the Class A American Association reporting to them in September. In the meantime, on August 13, 1910, Lefty’s 24th birthday, he tossed a 1-0 no-hitter against the Harrisonburg Senators at the York Fairgrounds. (11)

Lefty made his major league debut on April 14, 1911, pitching for the St. Louis Browns and losing to Cleveland 7-5. From 1911-1921, he was a steady, occasionally impressive pitcher in the high minors and a so-so performer in the majors. He pitched for St. Louis and the Cleveland Naps of the American League and Cincinnati and the Boston Braves of the National League. The highlight of his major league career came on September 11, 1915, when he pitched for Cincinnati and shut out Hall of Famer, Christy Matthewson, and the New York Giants 4-0. (12)

In 1921, George retired temporarily from baseball to pursue a career in business in York. However, he “un-retired” in 1923, pitching again for the York White Roses while still pursuing his business interests. The legend of Lefty George really coalesced during the years he played in the Class B New York-Pennsylvania League for York from 1923-1933. During this time, he pitched in 330 games, winning 165 and losing 98. Probably his best season was 1925 when he led the league with 27 victories and a 2.27 earned run average. He won 2 more games in the postseason as York defeated Williamsport 3 games to 1 in the playoffs to claim the league championship. At this time, local baseball fans were very loyal and almost rabid about their team and its heroes. Lefty’s antics on and off the mound also endeared him to fans not only in York but around the league.

One of George’s best assets was his unusual and almost comical, deceptive motion to first base. He would dazzle runners with that move, which one writer described as a “human piece of dough twisting itself into a pretzel.” Before the runner could tell what was going on, he had either been fooled into returning to base while Lefty delivered to the plate or picked off. (13) Lefty’s prominent Adam’s apple also attracted a lot of attention. One anonymous bard of the 1920’s wrote:

He’s built straight.

Only thing that protrudes is the Adam’s apple.

It bobs up and down like a cork on the ocean every time he swallows.

Lefty has the best balk motion in baseball.

Doesn’t have to wiggle a finger.

All he has to do is wave his Adam’s apple, and the runner dashes back to first. (14)

By the late 1920’s some of the fans in the league began to comment on Lefty’s age. Fans in Williamsport started to call him “Grand Paw.” One day, while pitching in Williamsport, Lefty got his revenge. He was hauled to the mound in a wheelchair, sporting a long, white, artificial beard. He dispatched the wheelchair to the sidelines and, much to the delight of the crowd, pitched three scoreless innings wearing the beard. (15) In 1933, at the age of 47, George again retired from professional baseball, but amazingly returned to pitch for the York White Roses in 1940. At this time, The Washington and Lee Alumni Magazine carried an article on the remarkable 54-year-old entitled “Plenty of Snap in Old Rubber Arm.” (November 1940) Lefty did not pitch professionally for the next two years, but in 1943, with a shortage of players due to World War II, he was again called upon to pitch. In his first starting assignment, June 16, 1943, he pitched a three-hit shutout against the Lancaster Red Roses. Altogether, Lefty appeared in 21 games for York in 1943, winning 7 and losing 8, not bad for a 57-year-old. (16) When he finally hung up his cleats in the spring of 1944, George had a lifetime minor league record of 327-287 and a 3.17 earned run average, one of the most remarkable careers in baseball history.

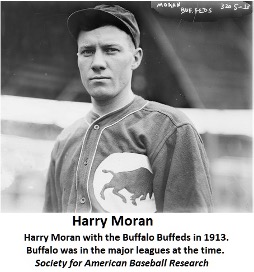

The next three major leaguers from W&L were all in school at the same time and played on a remarkable 1912 team, which won 19 games, the most by any Washington and Lee team until 1999 and still one of the highest single season winning percentages in W&L baseball history. The three players were Charles “Chuck” Tompkins, 1913 Law, Mark Stewart, 1915, and Harry Moran, 1914 Law. None of these men were great successes in the major or minor leagues. In fact, both Chuck Tompkins and Mark Stewart played in only one major league game each. Harry Moran was somewhat more successful, having played for three years in the majors. What makes Chuck Tompkins and Harry Moran distinctive is the fact that they played professional baseball while attending and graduating from the W&L Law School. In the summer of 1912, Harry played with the Detroit Tigers and the immortal Ty Cobb, while Chuck, having signed with Cincinnati, played one game with the Reds and several games with Toronto in the International League. Both Chuck and Harry helped coach the 1913 Generals’ squad, though neither played that year having exhausted their amateur status by playing pro ball the previous summer. ( 17) Apparently, by this time, the rules regarding amateur competition had become somewhat stiffer.

Al Pierrotti, 1923 BA, was one of the most remarkable athletes in the history of the university. He was an “all arounder” in the parlance of the day, excelling in four sports- football, basketball, baseball, and track and field. His model and that of many other athletes at the time was Jim Thorpe, considered by many the greatest all-around athlete in American history. At Washington and Lee, the man who is considered the greatest athlete in its history was Al’s teammate, Harry K. “Cy” Young. Cy also excelled in four sports and, again like Al, captained all four of these teams during his years in college. Cy won 16 letters in college, four letters in each of his four years, was a member of the Helms Foundation All-American Basketball team for 1917 and is a member of five athletic Halls of Fame. He is one of two W&L alums in the National College Football Hall of Fame, the other being Eddie Cameron. After college, Cy chose a career in business and coaching, ending his career as the first full-time Alumni Secretary at W&L. Al entered W&L in 1914, one year after Cy Young, and won 13 letters in college. He and Cy Young played on the undefeated football team of 1914 and the undefeated basketball team of 1917. (18) Although a member of the class of 1918, he left the university early in 1918 to volunteer for service in World War I. In 1918, he played football for the Boston Service All-Stars, (19) After the war, Pierrotti, like his hero, Jim Thorpe, played professional baseball and football for many years. He is one of 68 men to play both major league baseball and NFL football and the only W&L alumnus to do so.

In 1919, Pierrotti played with the Providence Grays of the Eastern League, and in 1920 and 1921 he was a pitcher with the Boston Braves (later the Milwaukee Braves and Atlanta Braves) of the National League. In 1922, he pitched in the minor leagues, having split his time between professional baseball and football for three years. In the fall of 1922, he returned full time to professional football, about which we shall say more later. Meanwhile, he continued to take classes at Washington and Lee, graduating in 1923. He eventually became a teacher and coach in his native Massachusetts, but still found time for other athletic endeavors. After retiring from pro football, Al took up professional wrestling in 1931. At the time, there were still some serious wrestlers in the professional ranks, but the sport was beginning to become the circus like spectacle we know today. In 1931 and 1932, he wrestled in 30 matches with a record of 15 wins, 14 losses, and one tie. His most famous match came on July 30, 1931, when he wrestled Jim Londos for the World Heavyweight Championship at the Coney Island Velodrome. Al lost this match, but stayed involved in wrestling, refereeing pro matches in the Boston area beginning in 1932. (20) Al again demonstrated his similarity to Jim Thorpe in having a real “barnstorming” athletic career, a more common occurrence in the 1920’s and 1930’s than it is today.

Fred Middleton “Penny” Bailey entered W&L in 1914 and played basketball and baseball in 1915. In spring 1916 he was called up by the Boston Braves. He played outfield for the Braves from 1916-1918 but had an undistinguished career. In 1918, he played for the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League. (21) He apparently returned to Washington and Lee in the fall of 1918 as he appears in the 1919 Calyx yearbook. Fred received his BA from the university in 1920.

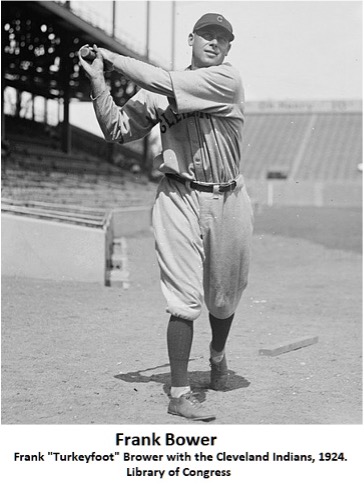

Frank “Turkey Foot” Brower, class of 1916, was a bird of a different feather. Although he only played in the major leagues for four seasons, he had a distinguished career. Brower entered W&L in the fall of 1912 and played on the baseball team of 1913. Following the end of the school year, he played semi-professional ball in Florida, batting over .500 for the summer. “Turkey” or “Turkey Foot”, his nickname from childhood, returned to the university and played for the baseball team in 1914, a violation of eligibility rules. In the spring of 1914, he signed with the St. Louis Cardinals, but played in the minor leagues from 1914-1917. During this period, he played outfield, first base, and occasional pitcher, roles which he later reprised in the majors. In January 1918 he enlisted in the navy, serving until the beginning of 1919. In 1919 and 1920, Frank played with Reading (PA) of the International League. In 1920 he had a .388 batting average and tied for the league lead in home runs with 22. He was then traded to the Senators and made his major league debut on August 4, 2020. He ended the season with a .311 average. In 1921 he had a .261 average with several homers, and in 1922 he played in 139 games, batted .293 and launched nine home runs. In 1923, he was traded to the Cleveland Indians where he had perhaps his finest year. On August 7, 1923, he went 6 for 6 in a game with the Senators, tying the American League record at that time. He is one of 117 major leaguers to have recorded 6 hits or more in a 9-inning game. For the season he batted .285 with 16 homers, one fewer than teammate, Tris Speaker, and in a tie for 11th place in the American League. In 1924, Brower was reduced to pinch hitting and an occasional start. Even so, he had a .280 average for the year. He also pitched from time to time. Frank ended his major league career with a lifetime average of .286, 206 runs scored, 30 home runs, 205 R.B.I.’s, and an on base percentage of .379. In 1925, the Indians sold him to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. This may seem like a step down, but the Seals were considered the class of minor league baseball at the time. Two of Brower’s teammates in San Francisco were Paul and Lloyd Waner, both future Hall of Famers. Later, Joe DiMaggio started his career there. In 1925, Frank batted .362 and launched 36 homers. The next year he hit .330 and had 16 home runs. From 1927 through 1929, he played with the Baltimore Orioles, then a minor league team, where he continued to hit for both average and power. (22) Frank Brower was clearly one of the best baseball players to ever come from W&L.

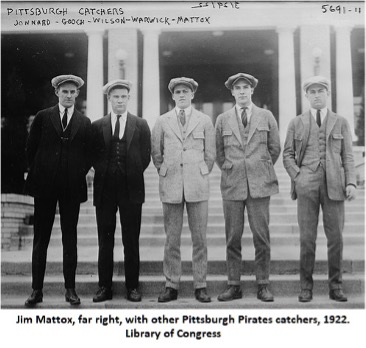

James Powell “Jim” Mattox, class of 1922, entered W&L in the fall of 1918. He played on the baseball team in spring, 1919 and on the football team in fall, 1919. His brother, Marvin Mattox, arrived at W&L in fall, 1919 and played on the football team with his brother that fall and on the baseball team with him in spring, 1920. (23) In 1921, Jim played as a catcher with Rochester in the International League and had a batting average of .344. In 1922 and 1923, he played with the Pittsburgh Pirates, but not a great deal. (24) The Mattox family was pretty remarkable. Marvin “Monk” Mattox played in the National Football League and in minor league baseball. Jim and Monk are the only two brothers in W&L history to play in the major leagues and the N.F.L. Another brother, Cloy, who did not attend Washington and Lee, also played briefly in the major leagues.

The last two major leaguers from Washington and Lee were 1937 classmates and members of a great baseball team in 1935, which went 17-4-2, won the Southern Conference, and had an even higher winning percentage than the 1912 team. These two men, George Emerson Dickman and Russell Dixon “Rusty” Peters, also had the longest major league careers of any alums. Dickman played for five years in the “Bigs,” while Rusty played for ten.

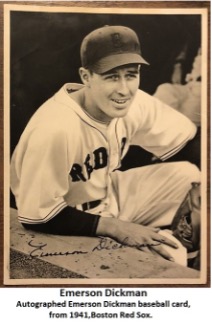

Emerson Dickman, class of 1937, entered the university in fall, 1933 and played college baseball for three years. He signed with the Boston Red Sox in spring, 1936 and played his entire major league career with them (1936, 1938-1941). He spent 1937 with Little Rock in the Class A Southern Association. Dickman enlisted in the Navy in early 1942 and spent the entire war in military service. After the war, Dickman did not return to pro baseball, but he did coach the Princeton Tigers team successfully from 1949-1951, where they had their only appearance in the College World Series in 1951. Later he had a career in the manufacturing and sale of radios and T.V.’s. His last job was as a group and season sales representative with the New York Yankees from 1975-1980. (25)

When Emerson first arrived with the Red Sox, the polymath catcher, Moe Berg, described him as “the finest prospect I’ve seen in a long time. He looks fine. I predict something for that fellow.” Berg was a very interesting individual. Described as “the brainiest guy in baseball”, he was a graduate of two Ivy League schools, spoke 10 languages, was a spy for the Office of Strategic Services ( O.S.S.) before and during World War II, and served occasionally with the C.I.A. after the war. (26) Berg was also a baseball coach and a keen observer of talent. In 1938, Dickman threw a shutout against the Indians, and in 1939 he had his best year with an 8-3 record and 5 saves. From his photos, it appears that Dickman was also very good looking, and one sportswriter compared to him to Robert Taylor, a Hollywood leading man of the era. This led to some ribbing from his teammates, but also to his marrying the model and cover girl, Connie Joannes in 1941. (27)

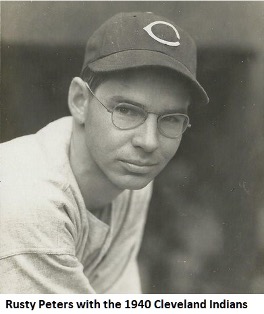

Russell “Rusty” Peters had the most successful big-league career of any W&L alum. Entering the university in January 1934, he played on both the 1934 and 1935 baseball teams. Rusty played minor league ball in 1935 and never returned to Washington and Lee. He received a trial from the Philadelphia Athletics in 1936 and impressed owner-manager Connie Mack enough to make the roster. That year he started out with a bang, batting over .300 and hitting two home runs in April, the second an inside the park homer. He later trailed off in his hitting and was sent to Columbus of the American Association where he did well and returned to the A’s in September. Peters played the entire 1937 season with the Athletics, averaging .260 with 17 doubles, 6 triples, 3 home runs, and 43 R.B.I.’s. One of the highlights of the season was a game against the Yankees on August 14th which Philadelphia won 12-6. Russ went 4-5, but lost a perfect day when Joe DiMaggio made a spectacular catch off him in the eighth inning. Peters was what is described as a “utility” player who played every infield position. Despite his solid 1937 campaign, he was sent to the Atlanta Crackers in 1938 and played under the Hall of Fame manager, Paul Richards. Rusty had a great year there in 1939, batting .316 with 38 doubles, 15 triples, 10 home runs, and 88 R.B.I.’s. He led the league in triples and was selected to the Southern Association’s All-Star team. Peters later admitted that this time in the minors was good for him: “Connie Mack gave me every chance, but I was just too young and inexperienced. I needed the two years under Paul Richards to become ready for the majors.” (28)

In 1940, Rusty was traded to the Cleveland Indians and played for them from 1940-1944. His natural position was shortstop, but he never played regularly at that position for the Indians. This was largely due to the fact that the manager and shortstop for Cleveland was the Hall of Famer, Lou Boudreau. In 1945-46 Rusty served with the American Army in Europe, returning to the Indians in September 1946. In 1947 he was sold to the St. Louis Browns and got off to a fine start, batting .340 in 39 games. Still, he was sold to Toledo of the American Association for the 1948 season and was soon traded to Indianapolis of the same league. He played for Indianapolis from 1948-51 and then retired from baseball. Although he had a major league career batting average of .236, he was a fine infielder and a consistent hitter. Lou Boudreau said of him: “On any other team in the league, Russ would have been a starting shortstop. But when I became the player-manager for Cleveland in 1942, there were two strikes against him. Russ was a great team player and a great individual. He never complained. He was a good infielder and a consistent hitter, although he didn’t hit with power.” (29) Unlike Emerson Dickman, Rusty Peters is not in the Washington and Lee Hall of Fame, but perhaps he should be.

When Rusty Peters finished his big-league season in 1947, he became the last W&L alum to make it to the major leagues. From 1877-1947, there were 12 alums who made it to “the show.” None of them were Hall of Famers or All-Stars, but several of them had respectable baseball careers. Eight of these played for the university during the period from 1908-1920, the so-called “golden era” of Washington and Lee athletics. This was also an era which produced many professional football players.

End Notes

1. John S. Patton, Jefferson, Cabell, and the University of Virginia (New York: Neale Publishing Co., 1906), 296-7, states that the University of Virginia Magazine, June 1868, says that the game was played in Charlottesville on this date.

2. “Match Game of Base Ball,” The Southern Collegian, April 13, 1869. This unsigned article does not specify the exact date of the game. The Southern Collegian was a student publication which was published until the end of the 19th century and revived later.:

3. See “Baseball,” The Southern Collegian, May 1892, 50, which states that W&L had an undefeated season against six different teams; See also “Sketch of the ’92 Ball Team, Champions of the South,” Washington and Lee Alumni Magazine, November 1926, 17-18.

4. William A. Cook, The Louisville Grays’ Scandal of 1877: The Taint of Gambling at the Dawn of the National League (Jefferson, NC: MacFarland and Co., 2005).

5. “Dan MacFarlan,” Baseball Reference, baseball-reference.com/players/m/mcfarda01.shml.

6. “Plenty of Snap in Old Rubber Arm,” The Washington and Lee Alumni Magazine, November 1940, 7, 22.

7. Gerald Tomlinson, “Lefty George: The Durable Duke of York,” Baseball Reference Journal, sabr.org/journal/article/lefty-george-the-durable-duke-of-york/.

8. “Mr. George’s Status,” Ring Tum Phi, April, 14, 1908.

9. See Ring Tum Phi, April 11, 18, 25, May 2, 23 on W&L baseball team and Lefty George.

10. “Washington and Lee Leaves for Games in the North,” The Richmond Times Dispatch, May 5, 1908, 7.

11. Jimmy Keenan, “Lefty George,” Society for American Baseball Research, sabr.org/bioproj/person/lefty-george/.

12. Ibid.

13. Jim McClure, “Lefty George, Baseball’s Methuselah, played for York White Roses,” York Daily Record, June 18, 2007.

14. Tomlinson, “Lefty George . . .”

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. See the 1912, 1913, and 1914 Calyx on the playing careers of these men. The Calyx was and is the Washington and Lee Yearbook; Harry Shoger, “Harry Moran,” Society for American Baseball Research, sabr.org/bioproj/person/harry-moran/0; “Chuck Tompkins,” Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia, arkbaseball.com/tiki-index.php?page=chuck+tompkins; “Mark Stewart,” Baseball Reference, baseball-reference.com/players/s/stewartma01.

18. For information on the college athletic careers of Al Pierrotti and Cy Young see the Washington and Lee Hall of Fame website, generalssports.com/honors/hall-of-fame.

19. Chris Serb, War Football: World War I and the Birth of the NFL (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2019), 198.

20. WrestlingData.com, wrestlingdata.com/index.php?befehl=bios&wrestler-17157&bild_1&details=7.

21. “Fred Bailey,” Baseball Reference, baseball-reference.com/bullpen/fred-bailey; Stats Crew, statscrew.com/minorbaseball/roster/t-tl15009/y-1918.

22. Chris Rainey, “Frank Brower,” Society for American Baseball Research, sabr.org/bioproj/person/frank-brower/

23. Calyx, 1920, 1921.

24. “Jim Mattox Stats,” Baseball Almanac, baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=mattoji01.

25. John Daly, “ Emerson Dickman,” Society for American Baseball Research, sabr.org/bioproj/person/emerson-dickman/

26. On Moe Berg see Nicholas Dawidoff, The Catcher was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg (New York: Vintage Books, 1994).

27. Daly, “Emerson Dickman.”

28. Jim Sargent, “Rusty Peters,” Society for American Baseball Research, sabr.org/bioproj/person/rusty-peters/

29. Ibid.

Neely Young is a 1966 graduate of Washington and Lee and holds a Ph.D. in History from Emory University. He is the author of two books and several articles. Neely is retired and living in Lexington.